Counting hours (or; how to work less when you want to work much)

I have worked a lot for the almost 2 years I’ve been at Sanity.io. Evenings, weekends, you name it. I know what you’re thinking: Another example of the exploitative tech startup churn.

But I’m not working a lot not because anyone has told me to do so. Rather on the opposite, I probably have at least 5 people, and among them mostly my managers telling me on a weekly basis that I should work less. The culture at Sanity.io isn't that you should crunch it on weekends and late hours, but rather, take time to plan and think on how to use the time one has on the right things. To get more done in less time with fewer distractions.

I don’t put in a lot of hours because I feel I have to prove myself either. Or because I’m hunting a promotion. I’m in the very privileged position where I’m fairly confident that I’m good at my job, and comfortable with the fact that I have a lot to learn. I put in a lot of hours because I inherently enjoy what I do. I look forward to it. It’s fun. It’s challenging. I learn a lot.

The hegemony of work-life (un)balance

It must be said, that this deep enjoyment is a relatively new thing for me. I have been at places where I have allowed myself to be consumed by work for all the wrong reasons. I have been through burn-out and depression, and used work as an escape from working with my own mental and emotional health and my tending my relationships. The stuff that Jason Lengstorf is writing about on his blog. Or Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson over at Basecamp. (I realize that this paragraph doesn't pass the Bechdel test - let me know if you know of someone that should’ve been included. Edit: I got recommened Ariana Huffington‘s talk about sleep)

There’s a push towards healthy work-life balance in the tech discourse, especially as a response to predatory practices and unreasonable expectations in the start-up world. VCs that suggest that getting a business up and running (with the kind of growth that’s expected in this part of entrepreneurship) may take a bit more effort than a 40 hour week will get hammered by people who thinks this is setting an unhealthy precedence. Both arguments have merrits.

Even if you remove high expecations of growth and insert somber Scandinavian values to work-life, building a company and a product will require more time and energy of the people involved compared to what you typically have in a “normal position” at established companies. That makes it all the more important that you create a culture where people can endure for the laung haul, and not hit the wall. And that is my experience of what one tries for at Sanity.io.

So I am not expected to be available on chat at all times (you set yourself away in focus mode when you need to get deep work done). Meetings are recognized as being expensive in terms of people’s time and attention, thus we try to come to them well-prepared and setting “hard-stops” is normal. If there isn't an agenda or something to actually discuss, we are happy to just call the meeting off.

So the drivers behind me putting in a lot of hours isn't found in the culture or expecations that surrounds me, it’s coming from within.

Vocation versus having a job

I do believe it’s crucial to take time to be someone for your family, partner, kids, friends, or pets. To exercise, sleep, taste things, travel into fiction, take part in culture, listen to music, work with your emotional pain, muse about your existence, and seek spiritual experiences (whatever they are for you). Work can get in the way of that. But sometimes the Venn-diagram between work and life will overlap. And then the dichotomy doesn't fit.

What I’m getting at is the idea of having found a vocation versus having a job. I suspect that many startups begin with founders and early-stage employees that very much has building a product and a business as a vocation, a calling. It might sound a bit precious, but I think you’ll often find the same drive among teachers, athletes, doctors and nurses, and in religious professions (from where the word originates).

The problem arises when you as a founder or early employee that has now entered into a mangager role, assume that it’s reasonable to expect the same calling or priorities from others. It’s probably cool if they do, but I believe you will be much happier if you accept that people can do great things in the hours you get to spend with them, and still turn off e-mail and Slack notifications to go home to be a dad, a partner, or to something completely different.

Now that I've entered into a manager role, I’m also worried that my behavior is modelling expectations that I expressively don’t have: I fully understand that other people that have other priorities for what they want and have to spend time on. In fact, I expect it to be a requirement for bring their best selves to work. I have no problem adjusting and planning for not being able to get in touch with a colleague after office hours.

If you find yourself in having a vocation in a job that you enjoy. That’s great! But remember that’s a privilege that you get to enjoy, and not a reasonable expectation that you can put on others. And to be honest, I find it much more inspiring to work with people who bring other forms of nerdery, interests, and hobbies to the table.

I need to be at work less

I probably have to do something with my own behaviour and prepare to be less present outside of working hours. I should reduce my activity on Slack in weekends, and be more mindful about when I engage my teammates in work-related discussions during evenings. And remember, we're talking about patterns here, not absolutes.

I brought my dilemma up to one of my managers: “I keep being told by all of you to work less, but I don't see that I'm really changing my behaviour. And I don't feel I’m on the path to burn-out, but I'm worried by the precedence it may set. So. How should we approach this differently?”

The advice I got was to approach my days more mindfully by do more planning, to think about what is really important, and to try to measure what I’m actually spending time on, like, in hours. These are activities that I traditionally haven’t eager to do. But as I have gotten more responsibility, I have slowly started to appreciate them more.

I already do fairly more planning. Both long-term, my upcoming week, my next day, and my day. I keep lists. It has helped me being less reactive, and I do less things that may feel urgent, but is probably not important. But spending as much time on more of the right things is only half of the challenge.

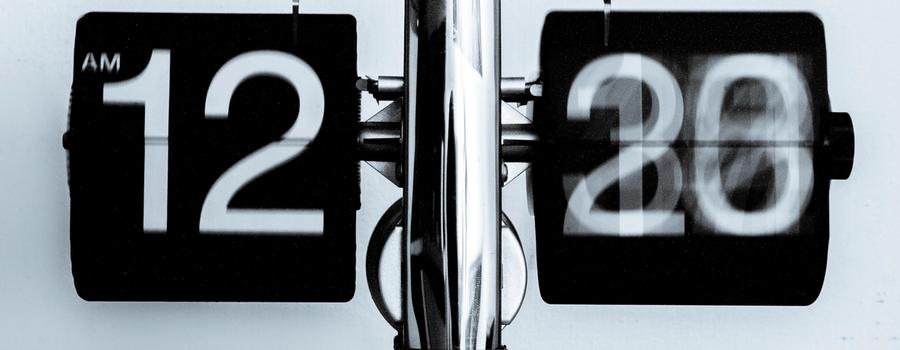

So I need to start with the same strategy as when you want to manage your weight, but instead of measuring how much energy I consume, I have to measure how many hours I spend on what things. I need to build some habits that doesn't depend as much as my immediate motivation, and set myself up for success for what I want to achieve. I must admit I kinda dread having to dedicate part of my cognitive brain to keep tally of what I’m doing, but all the better reason to do it probably.

Know thyself; start smol

I know that I probably will continue to thinking about new ideas at any hour, get the urge to get stuff down on paper, roam the web for inspiration, and all these things that you do in knowledge work. My main worry is that I’m modelling behaviour and unreasonable expecations for others, so what I need to fix first is how available and present I am: That begins with being off Slack during weekends.

Since I do a lot on US time (whilst living in Norway), I will also try to log onto work later in the morning, using the first few hours of the day to read, get some exercise, do chores, plan holidays, and so on. And the big one: I will also try to get into time tracking, and probably start small, by tracking just one type of activity, and take it from there.

These things are relatively small behavioural changes that I should be able to make happen. I have tried to make sure that the hardest one, starts with relatively low expectations. Start time tracking just one thing. Is the same as starting to run: It’s much easier to drag yourself out to run for 15 minutes than an hour. And getting out the door is the hardest part.

So this is me acknowledging that there is a door, and a run to be had. And that’s the first step.